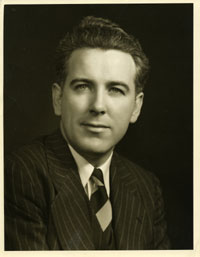

Optics Community Mourns the Loss of Jim Baker

Dr. James Gilbert Baker (1914-2005)

Dr. James Gilbert Baker, renowned astronomer and optical physicist, died June

29, 2005 at his home in Bedford , New Hampshire at the age of 90. Although his scientific

interest was astronomy, his extraordinary ability in optical design led to the creation

of hundreds of optical systems that supported astronomy, aerial reconnaissance, instant

photography (Polaroid SX70 camera), and the US space programs. He was the recipient

of numerous awards for his creative work.

He was born in Louisville , Kentucky , on Nov. 11, 1914, the fourth child of Jesse

B. Baker and Hattie M. Stallard. After graduating from Louisville duPont Manual High,

he went on to attend the University of Louisville major ing in Mathematics. He became very

close to an Astronomy Professor, Dr. Moore, and many times used his telescopes to

do nightly observations. While at the University he built mirrors for his own telescopes

and helped form the Louisville Astronomical Society in 1931. At the University of

Louisville , he also met his future wife, Elizabeth Katherine Breitenstein of Jefferson

County , Kentucky . He received his BA in 1935 at the height of the Depression. ing in Mathematics. He became very

close to an Astronomy Professor, Dr. Moore, and many times used his telescopes to

do nightly observations. While at the University he built mirrors for his own telescopes

and helped form the Louisville Astronomical Society in 1931. At the University of

Louisville , he also met his future wife, Elizabeth Katherine Breitenstein of Jefferson

County , Kentucky . He received his BA in 1935 at the height of the Depression.

He began his graduate work in astronomy at the Harvard College Observatory. After

his MA (1936), he was appointed a Junior Fellow (1937-1943) in the Prestigious Harvard

Society of Fellows. He received his PhD in 1942 from Harvard in rather an unusual

fashion that is worth repeating. During an Astronomy Department dinner, Dr. Harlow

Shapley (the director) asked him to give a talk. According to The Courier-Journal

Magazine, "Dr. Shapley stood up and proclaimed an on-the-spot departmental meeting

and asked for a vote on recommending Baker for a Ph.D. on the basis of the "oral

exam" he had just finished. The vote was unanimous." It was at Harvard

Observatory during this first stage of his career that he collaborated with Donald

H. Menzel, Lawrence H. Aller, and George H. Shortley on a landmark set of papers

on the Physical Processes in Gaseous Nebulae. In addition to his theoretical work,

he also began designing astronomical instruments with ever greater resolving powers

and wide-angle acceptance which he described as the "the royal way to new discoveries"1.

He is well known for the Baker-Schmidt telescope and the Baker Super Schmidt meteor

camera. He was also a co-author with George Z. Dimitroff of a book entitled "Telescopes

and Accessories" (1945). In 1948 he received an Honorary Doctorate from the

University of Louisville .

With the start of World War II, the US Army sought to establish an aerial reconnaissance

branch and placed the project in charge of Col. George W. Goddard. After months of

searching for an optical designer, he asked for a recommendation from Dr. Mees of

Eastman Kodak. Following the recommendations of Dr. Mees 2, Col. Goddard

found this friendly and unassuming 26 year old graduate student at Harvard, to be

the perfect candidate. He was impressed by Dr. Baker's originality in optical design

and provided him a small army research contract in early 1941 for a wide-angle camera

system. Goddard's "Victory Lens" project began on May 20, 1942 when he

visited Dr. Baker's office at Harvard Observatory and described the need for a lens

of f/2.5 covering a 5x5 plate to be made in huge quantities from rolled optical glass."

Multiple designs were developed during the war effort. A hands-on man, Dr. Baker

risked his life operating the cameras in many of the early test flights that carried

the camera systems in unpressurized compartments on aircraft. He was the director

of the Observatory Optical Project at Harvard University from 1943 to 1945. He began

his long consulting career with the Perkin Elmer Corporation during this period.

When the war ended, Harvard University decided to cease war-related projects and

subsequently, Dr. Baker's lab was moved to Boston University and was eventually spun

off as ITEK Corporation. However, he continued to be an associate professor and research

associate at Harvard from 1946 to 1949. In 1948 he received the Presidential Medal

for Merit for his work during World War II in the Office of Scientific Research and

Development.

In 1948, he moved to Orinda , California from Cambridge , Massachusetts and became

a research associate of Lick Observatory for two years. He returned to Harvard in

1950. He had spent thousands of hours doing ray trace calculations on a Marchant

calculator to produce his first aerial cameras. To replace the tedious calculations

by hand, Dr. Baker introduced the use of numerical computers in the field of optics.

His ray trace program was one of the first applications run on the Harvard Mark II

(1947) computer. Later on, he developed his own methodology to optimize the performance

of his optical designs. These optical design computer programs were a family affair,

developed under his direction by his own children to support his highly sophisticated

designs of the 1960's and 1970's.

For most of his career, Dr. Baker was involved with large system concepts covering

not only the camera, but the camera delivery systems as well. As the chairman of

U.S. Air Force Scientific Advisory Board, he recognized that national security requirements

would require optical designs of even greater resolving power using aircraft at extreme

altitudes. The need for such a plane resulted in the creation of the U-2 system consisting

of a plane and camera functioning as a unit to create panoramic high-resolution aerial

photographs. He formed Spica Incorporated in 1955 to perform the necessary optical

design work for the US Government. The final design was a 36-inch f/10 system. Dr.

Baker also designed the aircraft's periscope to allow the pilot to see his flight

path. By 1958, he was almost solely responsible for all the cameras used in photoreconnaissance

aircraft. He continued to serve on the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory

Board and on the Land Panel.

Before the launch of Sputnik, he designed the Baker-Nunn satellite-tracking camera

to support the Air Force's early satellite tracking and space surveillance networks.

Because of his foresight, cameras were in place to track the Sputnik Satellite in

October 1957. These cameras allowed the precise orbital determination of all orbiting

spacecraft for over three decades until the tracking cameras were retired from service.

He continued to advise top Government officials in the evolution of reconnaissance

systems during the 1960s and 1970s. He received a Space Pioneer Award from the US

Air Force. He received the Pioneers of National Reconnaissance (2000) Medal with

the citation " As a young Harvard astronomer, Dr. James G. Baker designed most

of the lenses and many of the cameras used in aerial over flights of 'denied territory'

enabling the success of the U.S. peacetime strategic reconnaissance policy."

Around 1968, he undertook a consulting contract with Polaroid Corporation after

Dr. Edwin Land persuaded him that only he could design the optical system for his

new SX-70 Land Camera TM . He was also responsible for the design of the Quintic

TM focusing system for the Polaroid Spectra Camera system that employed a revolutionary

combination of non-rotational aspherics to achieve focusing function.

In 1958 he became a Fellow of the Optical Society of America (OSA). In 1960 he

was elected President of the Society for one year and helped establish the Applied

Optics Journal. He was the recipient of numerous OSA awards, spanning the breadth

of the field, and has been honored with the Adolf Lomb Award, Ives Medal, Fraunhofer

Award, and Richardson Award. He was made an honorary member of OSA in 1993. He also

was the recipient of the 1978 Gold Medal, the highest award of the International

Society of Optical Engineers (SPIE). Furthermore, he was the Recipient of the Elliott

Cresson Medal of the Franklin Institute for his many innovations in astronomical

tools.

Dr. Baker was elected a Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1965), the

American Philosophical Society (1970), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

(1946), and the National Academy of Engineering (1979). He was a member of the American

Astronomical Society, the International Astronomical Union, and the Astronomical

Society of the Pacific. He authored numerous professional papers and has over fifty

US patents. He maintained his affiliation with Harvard Observatory and the Smithsonian

Astrophysical Observatory until he retired in 2003. Even after his retirement in

2003, he continued work at his home on a new telescope design that he told his family

he should have discovered in 1940.

Light was always his tool to the understanding of the Universe. An entry from

his personal observation log, Jan. 7, 1933, made after an evening of star gazing

reveals the pure inspiration of his efforts: "After all, it is the satisfaction

obtained which benefits humanity, more than any other thing. It is in the satisfaction

of greater human knowledge about the cosmos that the scientist is spurred on to greater

efforts." James Baker fulfilled the destiny he had foreseen in 1933, living

to see professional and amateur astronomers use his instruments and designs to further

the understanding of the cosmos. Whereas, he had not predicted that his cameras would

protect this nation for over sixty years.

He is survived by his wife, his four children and five grandchildren.

1 Oscar Bryant, Astronomical Designs, in Accent, the University of

Louisville College of Arts and Sciences Alumni Newsletter, Spring 1994

2p. 273, George W. Goddard,Brigadier General, Overview

|